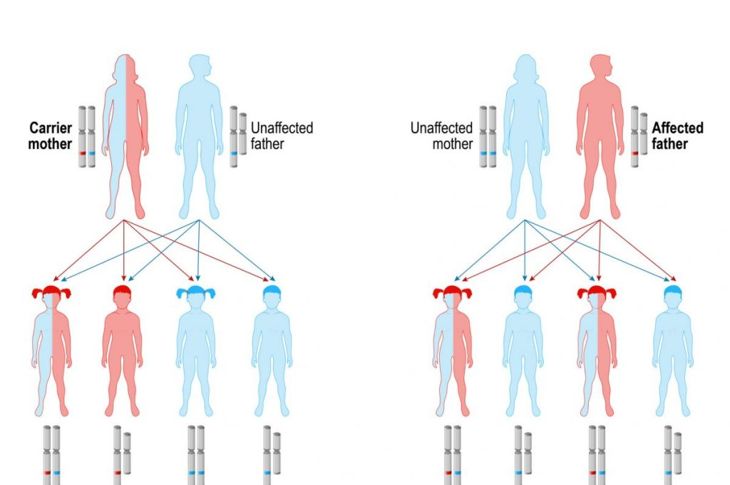

Globally, 1 in 12 men and 1 in 200 women have color vision deficiency or color blindness. Red-green color blindness is the most common form and is passed from mother to son via chromosome 23, known as the sex chromosome. There are many types of color blindness. Humans and most primates are trichromatic, meaning they have three light-sensitive proteins that help them distinguish between reds, blues, and greens. Some people with color blindness have defective trichromatic perception while others have dichromatic perception (two colors), monochromatic perception (one color), or none at all.

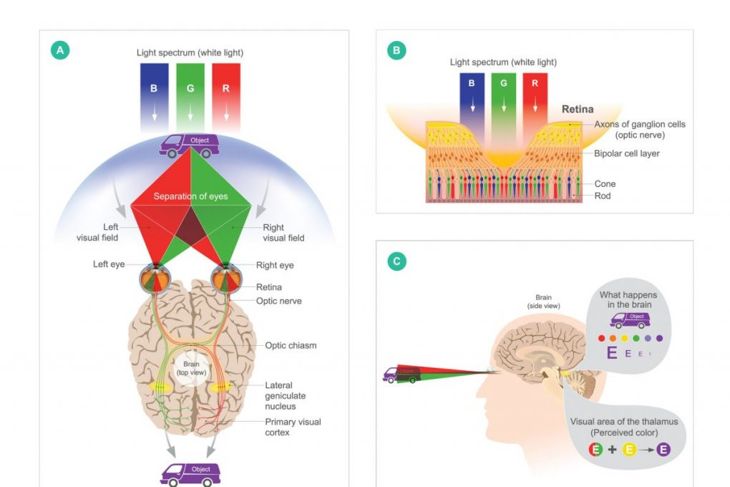

How Eyes See Color

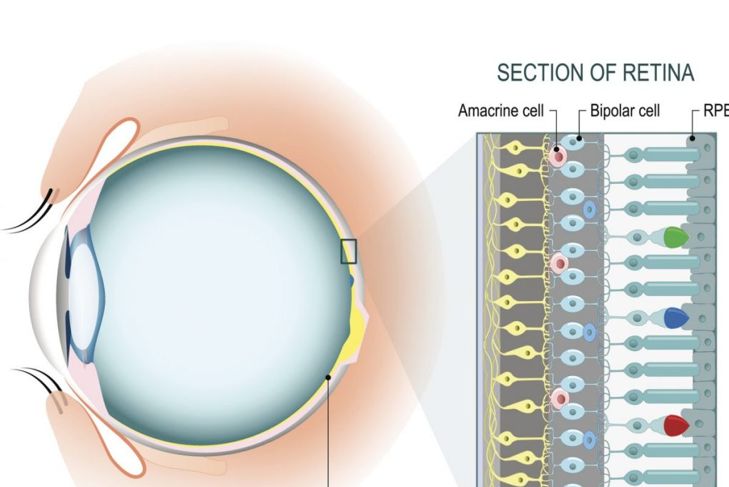

The human eye has a color spectrum of between 390 and 700 nanometers, which is a total of seven million colors. Within the fovea centralis, a small pit close to the optic nerve, are approximately six to seven million photoreceptors or cones of three types: S-cones, M-cones, and L-cones, with the letters standing for short, medium, and long-wavelength light. Wavelengths of reflected lights control the colors the eyes see. Any damage to or absence of the cones results in color blindness.

Causes of Color Blindness

Color blindness is both a genetic and acquired condition. With the genetic form, there is variation in how the cones respond to certain wavelengths. Acquired color blindness can develop due to diseases such as cataracts, glaucoma, and macular degeneration. It can also be due to acute damage, illness, or aging.

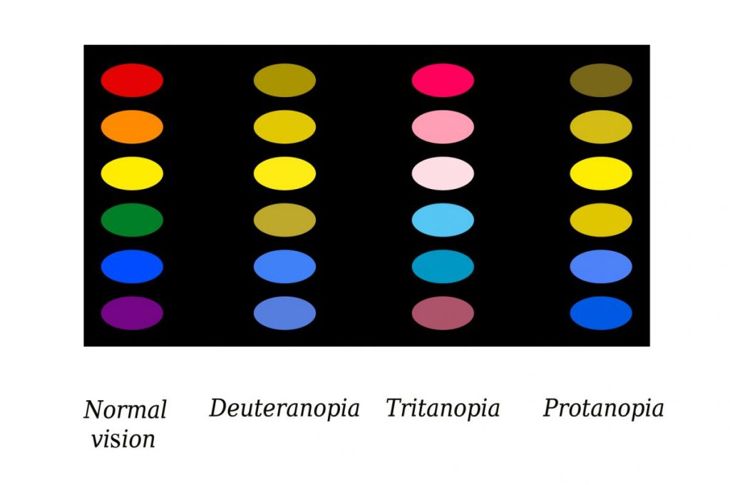

Protanomaly and Protanopia

People with red-green color blindness have a problem not only distinguishing between reds and greens, but also browns and oranges. Some even confuse blue and purple. There are two types of red-green blindness. Those who are sensitive to red light have protanomaly or protanopia. Protanomaly means the L-cones are defective while protanopia means they are missing and only short and medium-length cones are present. Those with protanomaly can see reddish brown instead of full red, as well as some purple and weaker greens. Those without L-cones do not see red or purple at all and green looks like yellow. Approximately one percent of men have this condition, compared to 0.02 to 0.03 percent of women.

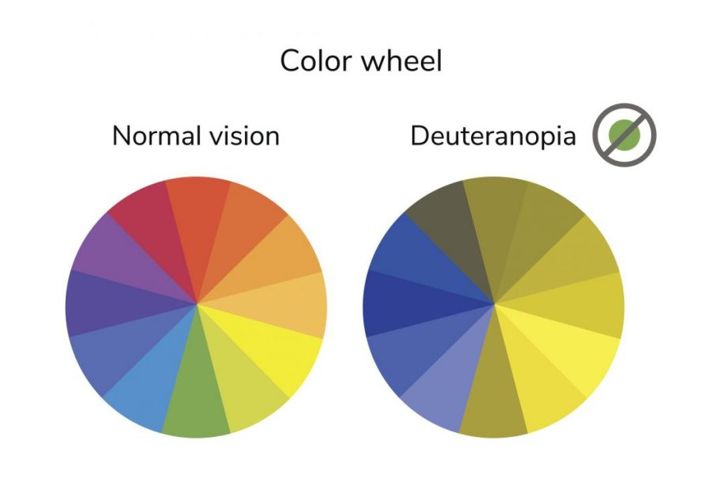

Deuteranomaly and Deuteranopia

Those with deuteranomaly have defective M-cones and are sensitive to green light. Just as with protanomaly, they see reddish brown and some purple. Green is weaker and less distinctive. Deuteranopia results in seeing far less red and purple and no green. Studies show some people have unilateral deuteranopia: color blindness in one eye. Between approximately one and five percent of men and 0.35 and one percent of women have this type of condition.

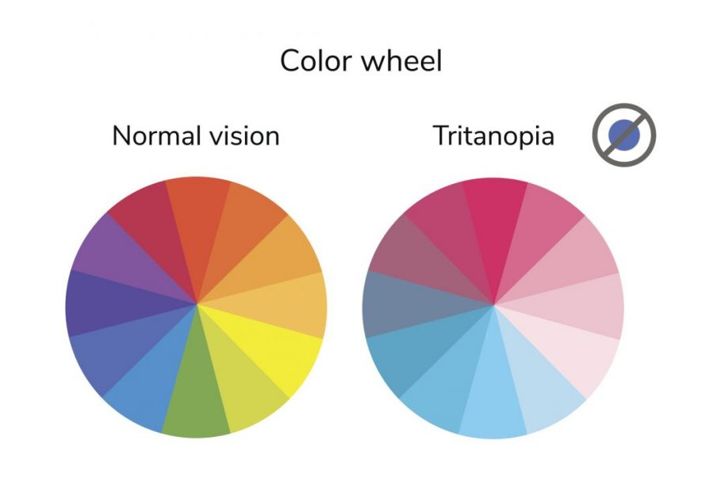

Tritanomaly and Tritanopia

Those affected by tritanomaly and tritanopia have damaged or missing S-cones and therefore confuse blue with green and yellow with violet. According to research, tritanomaly is rare, with a ratio of about one in 10,000. It has a chromosomal link, a defect in chromosome 7, which is not gender-linked. It is possible to acquire a tritan defect if the lens becomes less transparent due to age or a hard hit on the head.

Complete Color Blindness

Monochromacy or monochromatism is very rare. People with this condition see as shades of grey. However, monochromacy is an umbrella term: those with the deficiency may mix up colors, such as yellow and white, green and blue, or red and black. There are three forms of this extreme color blindness: rod monochromacy, blue-cone monochromacy, and cerebral achromatopsia.

Rod Monochromacy

Rods are the other type of photoreceptors in the eye, alongside cones. About 120 million rods in the eye are sensitive to light and are responsible for night vision. While rods aren’t sensitive to color, the light received affects the colors perceived. Rod monochromacy or congenital achromatopsia is severe color blindness from birth. Because the cones have photopigments — pigments in the retina that depend on illumination — the world is limited to black, white, and grey. These individuals are also uncomfortable in bright environments. Between one in 30,000 and one in 50,000 individuals have rod monochromacy.

Blue-Cone Monochromacy

Blue-cone monochromacy causes only the S-cones to transmit color, but they do not convey enough information to get a full-color picture. During evening and night hours, perception improves somewhat. Research indicates there are different types of this monochromacy, which affects approximately one in 100,000 people.

Cerebral Achromatopsia

Sometimes confused with congenital achromatopsia, cerebral achromatopsia is due to cerebral cortex damage. The main causes are ischemia or insufficient oxygen, or infarction or tissue death in the ventral occipitotemporal cortex due to lesions or stroke. However, doctors note approximately 72 percent of the cases of cerebral achromatopsia are accompanied by prosopagnosia, facial blindness.

Diagnosing Color Blindness

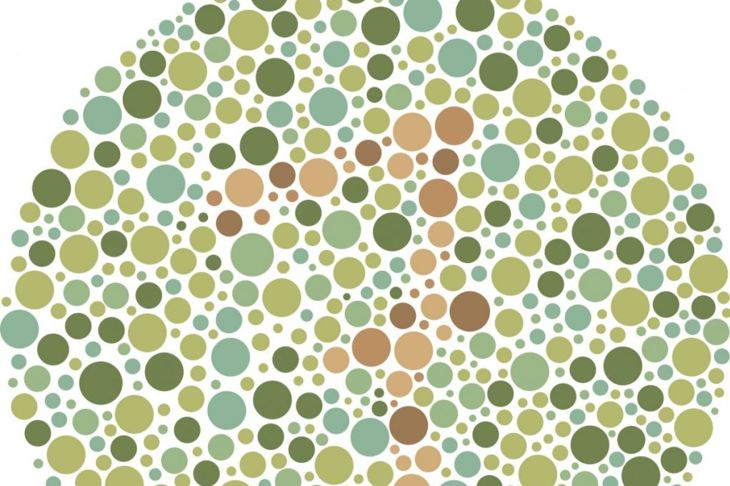

Four tests can diagnose color vision deficiency: Hardy-Rand-Rittler (HRR), Ishihara Color Plates, D-15, and Farnsworth-Munsell 100-hue disk-matching. HRR shows colored numbers against a colored background of dots to test for tritan defects. Ishihara tests are similar to HRR, but they test for red-green defects. The D-15 is a test of 15 color plates that must be put in the correct coded order while Farnsworth-Munsell tests chromatic discrimination between 100 different hues.

Home

Home Health

Health Diet & Nutrition

Diet & Nutrition Living Well

Living Well More

More